Humanitarian Doctor Tam Wai Jia on Denying Her Naysayers and the Power of Dreams

This article was first published in Tatler Asia by Chong Seow WeiThe Singapore-based medical doctor, author, artist and non-profit opens up about how dreams, fear and art intersect in her life.

It took a question about her life purpose from an editor of her latest book—which chronicles her global experiences as a humanitarian doctor—for Tam Wai Jia to realise what it was. “It has always been about dreams since I was 18: raising funds for the kids in Nepal, publishing my [picture] books, [starting my non-profit organisation] Kitesong Global,” says the mother-of-two. “What is the dream that's buried inside you that you want to give to the world?” And so she chose to name her next book Dream Brave.

The theme continued into her debut calligraphy exhibition, The Dreams Collection. It featured 10 artworks by her, displayed at the atrium of Clarke Quay Central first over the Lunar New Year this year to raise funds for her non-profit organisation Kitesong Global. The exhibition later moved to Square 2 at Novena, before its current place at Orchard Central until March 19. Through the exhibition, Tam displayed the determination and fearlessness she has always had when it comes to her life's work.

“This has been a theme my life, where people will tell me that what I want to do is reckless, but I’ll still do it anyway,” she says.

Tam first used art to engage and help others when she was 18, visiting Kathmandu in Nepal and living at a home for underprivileged or vulnerable girls. She recounts one night when she and the girls were evicted by the landlord because the home could not pay the increased rent. “The eviction happened every year and it’s traumatic for the girls. I realised that the only way to solve this problem was to raise funds for them to afford a permanent home,” she says.

So before she flew back to Singapore, Tam told the house parent in charge of the home that she had an idea of painting a picture book to raise the money they needed. “It sounded so silly, but he said, ‘I really believe in this idea and you must believe it too.’” That first book, Kitesong, raised $100,000 for the girls’ home within three months.

In the years since, Tam published three more picture books. During the Covid-19 pandemic, she launched My Brother SG, a platform to connect migrant workers with healthcare authorities and other relevant support organisations in Singapore.

She talks more about life coming full circle, her work as a humanitarian doctor and her experience with an eating disorder.

What was the moment that sparked your interest in humanitarian work?

Tam Wai Jia (WJ): When I was 17, I went on a youth expedition trip to Cambodia. I lived with a local family, who had a daughter who wanted to be a doctor, but they didn’t have the money to send her to school. I realised I had so much privilege, as I’d probably go to medical school if I got accepted, but she, being born in a different place, had little chance. That’s when I decided I wanted to do non-profit humanitarian work.

Was going to medical school something you had always wanted to do?

WJ: I really, really misunderstood my dad when he said that if I got straight As, I could do whatever I wanted in life. So I got straight As and told him I wanted to go to Lasalle [the arts school in Singapore], and he “fainted”.

He kept encouraging me to apply to medical school and I was initially heartbroken. But he convinced me. He said that when you’re a doctor, you can still be an artist. And for that, I’ll forever be grateful to him. Because he said if you’re an artist, it will be difficult for you to change your mind to become a doctor if you want to save lives. And I think I’ve come full circle now.

What was your experience with medical school like?

WJ: I hated it (laughs). It was too rigid and competitive, and a lot of rote memorising. I’m an experiential, kinetic learner. So for the first three years, I couldn’t cope with the learning style.

At the time, my family was also going through a very difficult business crisis. That was when I developed anorexia. I felt that I couldn’t control a lot of parts of my life. There was a lot of transition in the mix. I had to move into a dorm to stay by myself, and that was probably the lowest point [in my life] that I had. At 20, it was full-blown anorexia.

The turning point came when I wanted to end my life in the university dorm, but I thought to myself, is this why I came to medical school? What happened to Kitesong? What happened to help to better the lives of other people? And at that moment, I decided to hang on for just one more day, one more week, one more month. One of my mentors at the time also gave me a challenge. She said, if there’s nothing wrong with you, go see a doctor or a counsellor. So I self-enrolled into the hospital, but because my medical colleagues were doing rotations there, I begged them not to ward me. They saw me as an outpatient. So I underwent intensive outpatient therapy about once every week for a year.

My second picture book, A Taste of Rainbow, is actually about my recovery from anorexia. I drew throughout the time I was undergoing therapy.

With the book, you would be going public with your experience with anorexia. What made you feel comfortable enough to do that?

WJ: I decided I would because I knew there was a purpose bigger than me and maybe my story might help someone else.

The funny thing was, I had a visual thought at that time that I was speaking to a large crowd of people and it was overseas, and it was my journey to recovery. Many years later, when I was around 30, that vision came to pass.

I was at John Hopkins doing my masters in public health and I never pick up my phone because there were so many scam calls happening. But that day, I happen to and it was a lady from Nashville, who I have never met. She said she was gifted a copy of my book because her friend is the sister-in-law of a psychiatrist who is a colleague of my supervisor or something like that. It was like four degrees of separation. She invited me to be the keynote speaker of a conference she was organising about healing and body image.

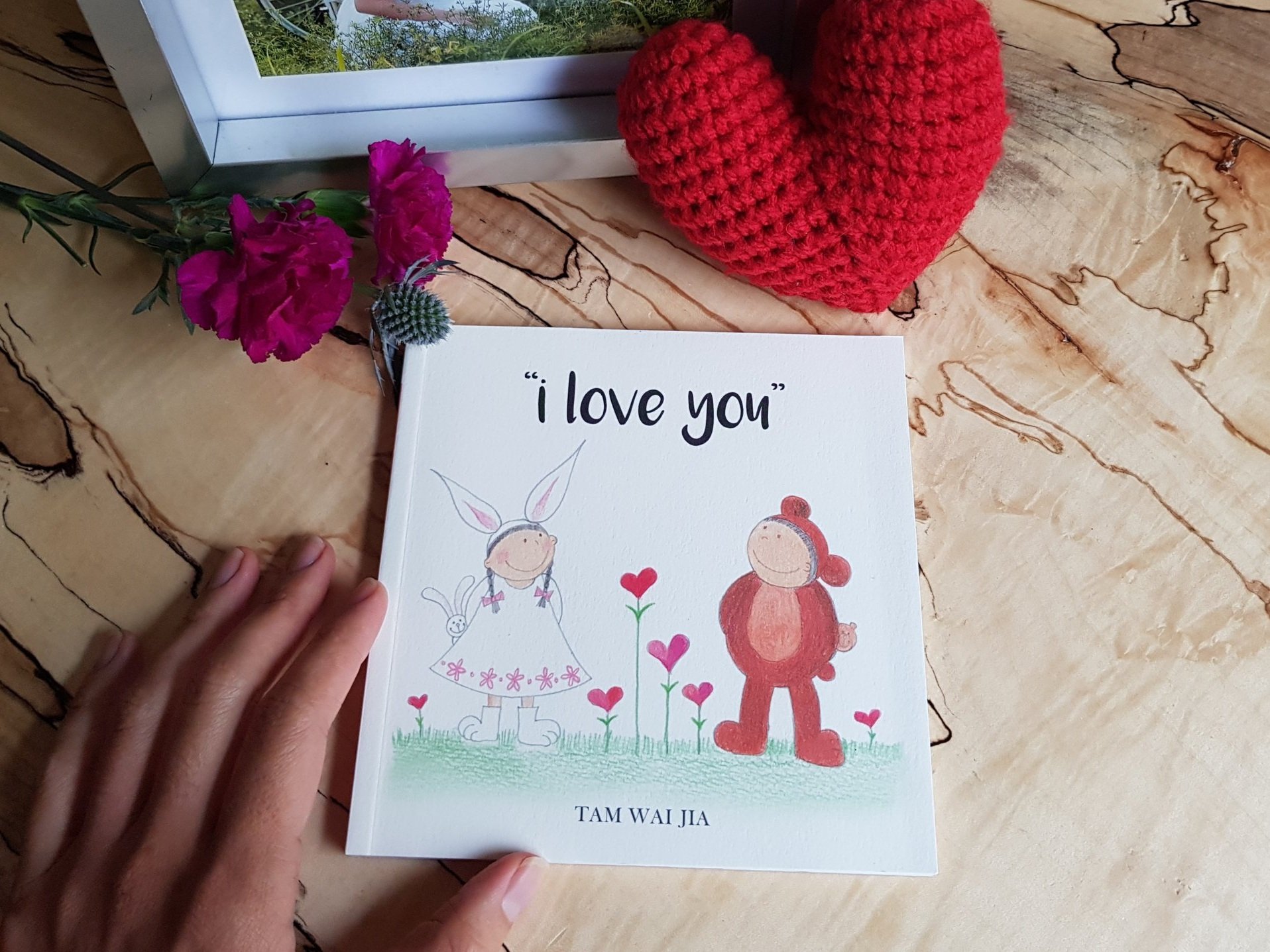

What’s the story behind your third picture book?

WJ: The book is titled I Love You and it was launched on my wedding day. My husband Cliff and I wanted to donate all of our wedding proceeds to two anti-sex trafficking ministries in Cambodia and India, and there was this huge uproar from our families. They said that it was a very bad and inauspicious way to start our wedding, but we did it anyway. In the end, we managed to raise S$60,000.

After you got married, you took a gap year from school to do humanitarian work in Uganda for a year. What was that like?

WJ: That whole year was very life-changing. It hit me then, the difference between success and significance. I mean I knew when I came back, my colleagues would be specialists or subspecialists, and I would just be left behind. There was also that pressure that my colleagues would be able to afford nice things.

So how did you move your mindset away from that?

WJ: I felt that I had sacrificed, but I remember there was one moment in Uganda when I was in a clinic and the doctor asked me why was I there and what was my specialty. When I told him I didn’t have one yet, he said I should have come when I did.

I remember I wept because I thought I had given up so much in my career for this, only to be told that I’m not good enough. But then, I also recall one of my mentors telling me that the world’s poorest need the world’s very best [doctors]. That was when I decided to do my master’s in public health at John Hopkins.

You had let go of two opportunities to apply to John Hopkins before you re-applied a third time. Tell us about the story there.

WJ: Yeah, I wasn’t able to afford the tuition at John Hopkins when I decided I wanted to enrol for my master’s after getting married. I had previously let go of two scholarships because I got married and because of Uganda.

My husband, however, encouraged me to apply a third time and eventually, I did get a scholarship from Fulbright. Years later, when I got to know the Fulbright board better, they told me that they selected my application because they thought my experience in Uganda showed my sincerity. And I was like, man, that was the very thing I was told would ruin my life and my career!

How did the John Hopkins experience help you with your non-profit afterwards?

WJ: It was the best decision I made, as it opened so many doors for me. It also kickstarted my journey to officially launch [my NGO] Kitesong Global. A lot of people were telling me to not start an NGO, as there would be so much admin work, too much bureaucracy, and you’ll have to hire staff, which you won’t be able to do. But this isn’t thinking about scale, it’s thinking about convenience or what’s good for you. That’s not what I want. I want impact.

It’s not enough to give what you have to the world. It’s important to give what you have in a way that reaches people. If they can’t receive it, what’s the point?

What is the mission of Kitesong Global?

WJ: What we do is empower young people to realise their dreams. We use art and storytelling to inspire people to believe in their dreams. Ultimately, the end goal is to impact vulnerable communities.

The world is looking for your gift, and if your gift can impact the world, what a tragedy it would be for you to hold back because of fear.

What work were you focused on during the pandemic?

WJ: Unfortunately, I wasn’t plugged into the medical system, so when they called for doctors to be deployed, I wasn’t involved. But one of my mentors reached out to ask if I could illustrate health booklets for migrant workers. At first, I thought, hey I’m a John Hopkins graduate, could you give me something more important to do than drawing? (Laughs) But I did it.

Then the chairperson of the World Health Organisation steering committee reached out and asked if I was a professional cartoonist. I told him that I was actually a doctor. So he made me the lead of risk communication and that changed my life.

So Kitesong Global was built on that. We were a non-profit organisation that already had translators and graphic designers all around the world, so we managed to produce tens of thousands of booklets, posters and digital formats in eight different languages for migrant workers in Singapore.

The WHO later deployed you to Africa last year right? What was that like?

WJ: Yes, I was deployed to Eswatini for six weeks as an RCCE (Risk Communication and Community Engagement) consultant. On my last day there, I wondered whether the trip was worth it, to miss the Chinese New Year holidays, to be away from my children.

But I realised that as parents, the decisions we make and the lives that we live impact our children because of the values that our actions speak of. Even though we made a sacrifice for me to go [to Africa], the message imprinted on [my children’s] lives far outweighed the cost we had to bear. So I don’t regret the trip. But Cliff did say he’ll only grant me one deployment a year (laughs).

Speaking of your husband, he has clearly been a strong pillar of support.

WJ: In our marriage, in a very paradoxical way, he is actually the leader. If he had not told me I should offer myself for deployment, I wouldn’t have done it. He was also the one who encouraged me to set up Kitesong Global. He’s like my life coach.

How long had you been thinking about holding an art exhibition?

WJ: It got triggered because last year, I realised that this year, in 2023, I needed about $200,000 to fund all of Kitesong’s programmes and pay my staff. We’re scaling and we can no longer rely on my personal savings or people’s goodwill anymore.

But why calligraphy?

WJ: One day, the idea of writing calligraphy being a way [to raise those funds] came to me, even though the art represented something very broken to me.

When I was five to 12 years old, I trained really hard in calligraphy, and the need to be perfect just became ingrained in me. Every Sunday, when I went to calligraphy class, no matter how well I did, my calligraphy teacher would return my work with tons of red marks. The whole experience was also very much about how do I win the next calligraphy competition. It was very stressful.

I decided to launch my calligraphy exhibition during the Lunar New Year because the holiday and calligraphy represented something similar. I associate them both with feelings of stress and tension.

What do you hope for people to take away from your exhibition?

WJ: I want people to look at the brokenness of their past with a new lens. It speaks to me of my own entrepreneurial and humanitarian journeys in that it is the brokenness in our journeys that makes us who we are. And we have a choice of turning our ashes into beauty.

Each of my artworks has a story. The anchor piece is the last piece in the series, 梦想 (meng xiang), which represents my life message. As you walk through the corridors of life, you will overcome hurdles and end up fulfilling your dreams.